About What Proportion of Southern White Families Owned No Slaves?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this department, you will be able to:

- Assess the distribution of wealth in the antebellum South

- Describe the southern culture of laurels

- Place the primary proslavery arguments in the years prior to the Civil War

During the antebellum years, wealthy southern planters formed an elite master class that wielded most of the economic and political power of the region. They created their ain standards of gentility and honor, defining ethics of southern white manhood and womanhood and shaping the civilisation of the South. To defend the system of forced labor on which their economical survival and genteel lifestyles depended, elite southerners adult several proslavery arguments that they levied at those who would meet the institution dismantled.

SLAVERY AND THE WHITE CLASS Construction

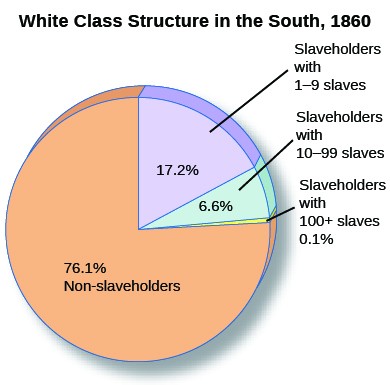

The S prospered, but its wealth was very unequally distributed. Upward social mobility did not be for the millions of slaves who produced a proficient portion of the nation's wealth, while poor southern whites envisioned a day when they might rise enough in the globe to own slaves of their ain. Considering of the cotton boom, there were more than millionaires per capita in the Mississippi River Valley by 1860 than anywhere else in the The states. However, in that aforementioned twelvemonth, only iii percent of whites endemic more than fifty slaves, and ii-thirds of white households in the S did not own any slaves at all. Distribution of wealth in the South became less democratic over time; fewer whites endemic slaves in 1860 than in 1840.

As the wealth of the antebellum South increased, it also became more unequally distributed, and an ever-smaller percentage of slaveholders held a substantial number of slaves.

At the tiptop of southern white club stood the planter elite, which comprised two groups. In the Upper S, an aloof gentry, generation upon generation of whom had grown upward with slavery, held a privileged identify. In the Deep Southward, an aristocracy group of slaveholders gained new wealth from cotton. Some members of this group hailed from established families in the eastern states (Virginia and the Carolinas), while others came from humbler backgrounds. South Carolinian Nathaniel Heyward, a wealthy rice planter and member of the aristocratic gentry, came from an established family and sat atop the pyramid of southern slaveholders. He amassed an enormous estate; in 1850, he owned more than eighteen hundred slaves. When he died in 1851, he left an estate worth more than $2 million (approximately $63 million in 2014 dollars).

As cotton product increased, new wealth flowed to the cotton planters. These planters became the staunchest defenders of slavery, and every bit their wealth grew, they gained considerable political power.

One fellow member of the planter elite was Edward Lloyd V, who came from an established and wealthy family of Talbot County, Maryland. Lloyd had inherited his position rather than ascension to it through his own labors. His hundreds of slaves formed a crucial office of his wealth. Like many of the planter aristocracy, Lloyd's plantation was a masterpiece of elegant architecture and gardens.

The 1000 house of Edward Lloyd V advertised the status and wealth of its owner. In its heyday, the Lloyd family's plantation boasted holdings of forty-ii 1000 acres and ane chiliad slaves.

One of the slaves on Lloyd'due south plantation was Frederick Douglass, who escaped in 1838 and became an abolitionist leader, writer, statesman, and orator in the North. In his autobiography, Douglass described the plantation's elaborate gardens and racehorses, but as well its underfed and brutalized slave population. Lloyd provided employment opportunities to other whites in Talbot County, many of whom served equally slave traders and the "slave breakers" entrusted with beating and overworking unruly slaves into submission. Similar other members of the planter elite, Lloyd himself served in a multifariousness of local and national political offices. He was governor of Maryland from 1809 to 1811, a member of the House of Representatives from 1807 to 1809, and a senator from 1819 to 1826. As a representative and a senator, Lloyd dedicated slavery as the foundation of the American economy.

Wealthy plantation owners similar Lloyd came close to forming an American ruling class in the years before the Ceremonious War. They helped shape foreign and domestic policy with ane goal in view: to expand the power and reach of the cotton kingdom of the South. Socially, they cultivated a refined manner and believed whites, especially members of their grade, should non perform manual labor. Rather, they created an identity for themselves based on a world of leisure in which horse racing and entertainment mattered greatly, and where the enslavement of others was the boulder of civilization.

In this painting by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, a yeoman farmer carrying a scythe follows his livestock down the route.

Below the wealthy planters were the yeoman farmers, or minor landowners. Below yeomen were poor, landless whites, who made upwards the bulk of whites in the South. These landless white men dreamed of owning land and slaves and served as slave overseers, drivers, and traders in the southern economy. In fact, owning state and slaves provided one of the only opportunities for upward social and economical mobility. In the South, living the American dream meant possessing slaves, producing cotton, and owning country.

Despite this unequal distribution of wealth, not-slaveholding whites shared with white planters a common set up of values, almost notably a belief in white supremacy. Whites, whether rich or poor, were bound together past racism. Slavery defused course tensions amid them, because no matter how poor they were, white southerners had race in common with the mighty plantation owners. Not-slaveholders accustomed the dominion of the planters as defenders of their shared interest in maintaining a racial bureaucracy. Significantly, all whites were besides bound together past the constant, prevailing fear of slave uprisings.

D. R. Hundley on the Southern Yeoman

D. R. Hundley was a well-educated planter, lawyer, and banker from Alabama. Something of an amateur sociologist, he argued against the mutual northern supposition that the South was made upwards exclusively of ii tiers of white residents: the very wealthy planter class and the very poor landless whites. In his 1860 volume, Social Relations in Our Southern States, Hundley describes what he calls the "Southern Yeomen," a social group he insists is roughly equivalent to the middle-grade farmers of the North.

Merely you accept no Yeomen in the South, my dear Sir? Beg your pardon, our dear Sir, just nosotros have—hosts of them. I idea you lot had only poor White Trash? Yeah, we dare say as much—and that the moon is made of greenish cheese! . . . Know, then, that the Poor Whites of the Southward plant a split class to themselves; the Southern Yeomen are every bit distinct from them as the Southern Gentleman is from the Cotton Snob. Certainly the Southern Yeomen are nearly always poor, at least then far as this world's goods are to be taken into account. As a general thing they own no slaves; and even in case they do, the wealthiest of them rarely possess more than from ten to 15. . . . The Southern Yeoman much resembles in his speech, religious opinions, household arrangements, indoor sports, and family unit traditions, the center class farmers of the Northern States. He is fully as intelligent as the latter, and is on the whole much better versed in the lore of politics and the provisions of our Federal and State Constitutions. . . . [A]lthough not as a class pecuniarily interested in slave property, the Southern Yeomanry are nearly unanimously pro-slavery in sentiment. Nor do we see how whatsoever honest, thoughtful person can reasonably find mistake with them on this account.

—D. R. Hundley, Social Relations in Our Southern States, 1860

What elements of social relations in the South is Hundley attempting to emphasize for his readers? In what respects might his position as an educated and wealthy planter influence his understanding of social relations in the South?

Because race bound all whites together as members of the chief race, non-slaveholding whites took function in civil duties. They served on juries and voted. They besides engaged in the daily rounds of maintaining slavery by serving on neighborhood patrols to ensure that slaves did not escape and that rebellions did not occur. The practical consequence of such activities was that the institution of slavery, and its perpetuation, became a source of commonality amidst dissimilar economic and social tiers that otherwise were separated by a gulf of difference.

Southern planters exerted a powerful influence on the federal government. Seven of the offset 11 presidents owned slaves, and more than than half of the Supreme Court justices who served on the court from its inception to the Civil War came from slaveholding states. Still, southern white yeoman farmers mostly did not support an agile federal government. They were suspicious of the state bank and supported President Jackson's dismantling of the Second Bank of the Usa. They also did non back up taxes to create internal improvements such every bit canals and railroads; to them, regime involvement in the economic life of the nation disrupted what they perceived as the natural workings of the economy. They also feared a strong national government might tamper with slavery.

Planters operated inside a larger backer society, but the labor system they used to produce goods—that is, slavery—was similar to systems that existed before capitalism, such every bit feudalism and serfdom. Under commercialism, gratuitous workers are paid for their labor (past owners of capital) to produce commodities; the money from the auction of the appurtenances is used to pay for the work performed. Every bit slaves did not reap whatsoever earnings from their forced labor, some economic historians consider the antebellum plantation system a "pre-backer" organization.

Award IN THE S

"The Modern Tribunal and Czar of Men'south Differences," an illustration that appeared on the cover of The Mascot, a paper published in nineteenth-century New Orleans, reveals the importance of dueling in southern culture; it shows men bowing before an chantry on which are laid a pistol and knife.

A complicated code of honor among privileged white southerners, dictating the behavior and behavior of "gentlemen" and "ladies," adult in the antebellum years. Maintaining appearances and reputation was supremely of import. It tin be argued that, equally in many societies, the concept of honor in the antebellum South had much to do with control over dependents, whether slaves, wives, or relatives. Defending their accolade and ensuring that they received proper respect became preoccupations of whites in the slaveholding Due south. To question another man's assertions was to call his award and reputation into question. Insults in the form of words or behavior, such as calling someone a coward, could trigger a rupture that might well end on the dueling ground. Dueling had largely disappeared in the antebellum N by the early nineteenth century, but it remained an of import part of the southern code of laurels through the Civil State of war years. Southern white men, especially those of high social condition, settled their differences with duels, earlier which antagonists ordinarily attempted reconciliation, frequently through the exchange of letters addressing the alleged insult. If the challenger was not satisfied by the exchange, a duel would often result.

The dispute between South Carolina's James Hammond and his one-time friend (and brother-in-police) Wade Hampton II illustrates the southern culture of honour and the identify of the duel in that culture. A potent friendship bound Hammond and Hampton together. Both stood at the acme of S Carolina'southward social club every bit successful, married plantation owners involved in state politics. Prior to his ballot as governor of the state in 1842, Hammond became sexually involved with each of Hampton'south four teenage daughters, who were his nieces past marriage. "[A]ll of them rushing on every occasion into my artillery," Hammond confided in his individual diary, "covering me with kisses, lolling on my lap, pressing their bodies almost into mine . . . and permitting my hands to stray unchecked." Hampton found out about these dalliances, and in keeping with the lawmaking of laurels, could take demanded a duel with Hammond. Yet, Hampton instead tried to use the liaisons to destroy his former friend politically. This effort proved disastrous for Hampton, because it represented a violation of the southern lawmaking of honor. "As matters now stand up," Hammond wrote, "he [Hampton] is a convicted dastard who, non having nerve to redress his ain wrongs, put forward bullies to do it for him. . . . To claiming me [to a duel] would be to throw himself upon my mercy for he knows I am non bound to meet him [for a duel]." Because Hampton's beliefs marked him equally a man who lacked honor, Hammond was no longer bound to meet Hampton in a duel fifty-fifty if Hampton were to need one. Hammond's reputation, though tarnished, remained high in the esteem of South Carolinians, and the governor went on to serve as a U.South. senator from 1857 to 1860. Every bit for the four Hampton daughters, they never married; their names were disgraced, not merely by the whispered-about scandal but by their male parent'southward actions in response to information technology; and no man of honor in South Carolina would stoop so low as to ally them.

GENDER AND THE SOUTHERN HOUSEHOLD

The antebellum South was an especially male-dominated club. Far more than in the North, southern men, peculiarly wealthy planters, were patriarchs and sovereigns of their own household. Among the white members of the household, labor and daily ritual conformed to rigid gender delineations. Men represented their household in the larger world of politics, business concern, and war. Within the family unit, the patriarchal male was the ultimate say-so. White women were relegated to the household and lived nether the thumb and protection of the male patriarch. The platonic southern lady conformed to her prescribed gender role, a role that was largely domestic and subservient. While responsibilities and experiences varied beyond different social tiers, women's subordinate land in relation to the male patriarch remained the same.

Writers in the antebellum period were fond of celebrating the paradigm of the ideal southern adult female. I such writer, Thomas Roderick Dew, president of Virginia's College of William and Mary in the mid-nineteenth century, wrote approvingly of the virtue of southern women, a virtue he concluded derived from their natural weakness, piety, grace, and modesty. In his Dissertation on the Characteristic Differences Betwixt the Sexes, he writes that southern women derive their power not by

leading armies to combat, or of enabling her to bring into more than formidable activity the physical power which nature has conferred on her. No! It is but the ameliorate to perfect all those feminine graces, all those fascinating attributes, which render her the center of allure, and which delight and charm all those who breathe the temper in which she moves; and, in the linguistic communication of Mr. Burke, would make ten m swords spring from their scabbards to avenge the insult that might be offered to her. By her very meekness and beauty does she subdue all around her.

Such pop idealizations of elite southern white women, however, are difficult to reconcile with their lived experience: in their ain words, these women frequently described the trauma of childbirth, the loss of children, and the loneliness of the plantation.

This cover illustration from Harper's Weekly in 1861 shows the ideal of southern womanhood.

Louisa Cheves McCord'southward "Adult female's Progress"

Louisa Cheves McCord was built-in in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1810. A child of some privilege in the South, she received an excellent education and became a prolific author. As the excerpt from her poem "Adult female'south Progress" indicates, some southern women also contributed to the idealization of southern white womanhood.

Sweet Sister! stoop not one thousand to be a homo!

Man has his place as woman hers; and she

As fabricated to comfort, minister and aid;

Moulded for gentler duties, ill fulfils

His jarring destinies. Her mission is

To labour and to pray; to help, to heal,

To soothe, to behave; patient, with smiles, to endure;

And with self-abnegation noble lose

Her private involvement in the dearer weal

Of those she loves and lives for. Telephone call not this—

(The all-fulfilling of her destiny;

She the globe'south soothing mother)—call it not,

With scorn and mocking sneer, a drudgery.

The ribald natural language profanes Sky's holiest things,

But holy all the same they are. The lowliest tasks

Are sanctified in nobly acting them.

Christ washed the apostles' feet, not thus cast shame

Upon the God-like in him. Woman lives

Human'southward constant prophet. If her life be truthful

And based upon the instincts of her being,

She is a living sermon of that truth

Which ever through her gentle deportment speaks,

That life is given to labour and to dear.—Louisa Susanna Cheves McCord, "Woman'southward Progress," 1853

What womanly virtues does Louisa Cheves McCord emphasize? How might her social condition, as an educated southern woman of great privilege, influence her understanding of gender relations in the South?

For slaveholding whites, the male-dominated household operated to protect gendered divisions and prevalent gender norms; for slave women, still, the same system exposed them to brutality and frequent sexual domination. The demands on the labor of slave women made it impossible for them to perform the function of domestic caretaker that was and then idealized by southern men. That slaveholders put them out into the fields, where they oft performed piece of work traditionally thought of as male, reflected niggling the ideal image of gentleness and delicacy reserved for white women. Nor did the slave adult female's office every bit girl, wife, or mother garner whatsoever patriarchal protection. Each of these roles and the relationships they divers was discipline to the prerogative of a master, who could freely violate enslaved women'southward persons, sell off their children, or separate them from their families.

DEFENDING SLAVERY

John C. Calhoun, shown here in a ca. 1845 portrait by George Alexander Healy, defended states' rights, especially the correct of the southern states to protect slavery from a hostile northern majority.

With the ascent of commonwealth during the Jacksonian era in the 1830s, slaveholders worried almost the ability of the bulk. If political power went to a majority that was hostile to slavery, the South—and the honor of white southerners—would be imperiled. White southerners smashing on preserving the institution of slavery bristled at what they perceived to be northern attempts to deprive them of their livelihood. Powerful southerners similar South Carolinian John C. Calhoun highlighted laws like the Tariff of 1828 as evidence of the North's desire to destroy the southern economic system and, by extension, its culture. Such a tariff, he and others concluded, would disproportionately harm the South, which relied heavily on imports, and do good the North, which would receive protections for its manufacturing centers. The tariff appeared to open the door for other federal initiatives, including the abolition of slavery. Because of this perceived threat to southern club, Calhoun argued that states could nullify federal laws. This belief illustrated the importance of united states of america' rights argument to the southern states. Information technology besides showed slaveholders' willingness to unite against the federal government when they believed it acted unjustly against their interests.

Every bit the nation expanded in the 1830s and 1840s, the writings of abolitionists—a small just song group of northerners committed to ending slavery—reached a larger national audition. White southerners responded by putting forth arguments in defence of slavery, their fashion of life, and their honor. Calhoun became a leading political theorist defending slavery and the rights of the Due south, which he saw every bit containing an increasingly embattled minority. He advanced the idea of a concurrent majority, a majority of a split up region (that would otherwise be in the minority of the nation) with the ability to veto or disallow legislation put frontwards past a hostile bulk.

Calhoun's idea of the concurrent majority constitute full expression in his 1850 essay "Disquisition on Government." In this treatise, he wrote about government as a necessary means to ensure the preservation of society, since order existed to "preserve and protect our race." If government grew hostile to club, then a concurrent majority had to take action, including forming a new regime. "Disquisition on Government" advanced a profoundly anti-democratic argument. It illustrates southern leaders' intense suspicion of democratic majorities and their ability to effect legislation that would challenge southern interests.

Go to the Internet Archive to read John C. Calhoun's "Disquisition on Regime." Why do yous think he proposed the creation of a concurrent majority?

White southerners reacted strongly to abolitionists' attacks on slavery. In making their defence of slavery, they critiqued wage labor in the North. They argued that the Industrial Revolution had brought most a new type of slavery—wage slavery—and that this form of "slavery" was far worse than the slave labor used on southern plantations. Defenders of the institution likewise lashed out direct at abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison for daring to call into question their way of life. Indeed, Virginians cited Garrison every bit the instigator of Nat Turner'due south 1831 rebellion.

The Virginian George Fitzhugh contributed to the defense of slavery with his book Sociology for the Due south, or the Failure of Gratis Gild (1854). Fitzhugh argued that laissez-faire capitalism, equally celebrated past Adam Smith, benefited only the quick-witted and intelligent, leaving the ignorant at a huge disadvantage. Slaveholders, he argued, took care of the ignorant—in Fitzhugh'southward argument, the slaves of the South. Southerners provided slaves with care from birth to death, he asserted; this offered a stark contrast to the wage slavery of the Northward, where workers were at the mercy of economic forces across their control. Fitzhugh's ideas exemplified southern notions of paternalism.

George Fitzhugh'southward Defense of Slavery

George Fitzhugh, a southern author of social treatises, was a staunch supporter of slavery, not as a necessary evil but as what he argued was a necessary adept, a way to accept care of slaves and go on them from existence a brunt on guild. He published Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society in 1854, in which he laid out what he believed to exist the benefits of slavery to both the slaves and society as a whole. According to Fitzhugh:

[I]t is articulate the Athenian democracy would not suit a negro nation, nor volition the government of mere constabulary suffice for the individual negro. He is but a grown up child and must be governed equally a child . . . The master occupies towards him the place of parent or guardian. . . . The negro is improvident; will not lay up in summertime for the wants of winter; will not accrue in youth for the exigencies of age. He would go an insufferable brunt to society. Order has the right to prevent this, and can only practise so past subjecting him to domestic slavery.

In the last place, the negro race is inferior to the white race, and living in their midst, they would be far outstripped or outwitted in the hunt of costless contest. . . . Our negroes are not just meliorate off as to physical condolement than free laborers, just their moral status is better.

What arguments does Fitzhugh use to promote slavery? What basic premise underlies his ideas? Can you think of a modern parallel to Fitzhugh's statement?

The North also produced defenders of slavery, including Louis Agassiz, a Harvard professor of zoology and geology. Agassiz helped to popularize polygenism, the idea that different human races came from dissever origins. According to this formulation, no single man family unit origin existed, and blacks made upward a race wholly split up from the white race. Agassiz's notion gained widespread popularity in the 1850s with the 1854 publication of George Gliddon and Josiah Nott's Types of Mankind and other books. The theory of polygenism codified racism, giving the notion of black inferiority the lofty pall of science. One pop abet of the thought posited that blacks occupied a place in evolution betwixt the Greeks and chimpanzees.

This 1857 illustration by an advocate of polygenism indicates that the "Negro" occupies a place between the Greeks and chimpanzees. What does this image reveal about the methods of those who advocated polygenism?

Section Summary

Although a minor white elite owned the vast majority of slaves in the S, and most other whites could merely aspire to slaveholders' wealth and status, slavery shaped the social life of all white southerners in profound means. Southern civilisation valued a behavioral code in which men'south accolade, based on the domination of others and the protection of southern white womanhood, stood as the highest good. Slavery also decreased class tensions, bounden whites together on the basis of race despite their inequalities of wealth. Several defenses of slavery were prevalent in the antebellum era, including Calhoun'south statement that the South's "concurrent majority" could overrule federal legislation accounted hostile to southern interests; the notion that slaveholders' care of their chattel made slaves better off than wage workers in the North; and the greatly racist ideas underlying polygenism.

https://www.openassessments.org/assessments/984

Review Question

- How did defenders of slavery use the concept of paternalism to structure their ideas?

Answer to Review Question

- Defenders of slavery, such as George Fitzhugh, argued that only the clever and the vivid could truly benefit inside a laissez-faire economic system. Premising their argument on the notion that slaves were, by nature, intellectually junior and less able to compete, such defenders maintained that slaves were ameliorate off in the care of paternalistic masters. While northern workers establish themselves trapped in wage slavery, they argued, southern slaves' needs—for nutrient, clothing, and shelter, among other things—were met by their masters' paternal benevolence.

Glossary

concurrent majoritya majority of a split region (that would otherwise be in the minority of the nation) with the ability to veto or disallow legislation put forward past a hostile majority

polygenismthe idea that blacks and whites come from dissimilar origins

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ushistory1os2xmaster/chapter/wealth-and-culture-in-the-south/

0 Response to "About What Proportion of Southern White Families Owned No Slaves?"

Post a Comment